IF THE CRITERION YOU USE to measure the majesty of mountains is simple math, then the greatest peak on earth is Everest; at 29,035 feet, it surpasses K2 by 785 feet. If popularity is the gauge, the answer seems equally obvious: More than 1,600 people have been to the top of Everest, claiming all manner of "firsts," including but by no means limited to: the first one-legged summiter, the first one-armed summiter, the first person to sleep on the summit, the first live TV broadcast from the summit, the first person to make five summits in five consecutive years, and the first husband-and-wife team to fling themselves off the summit in a tandem paraglider. This year, another 262 climbers have reached the highest point on the planet as of press time. And in 2008, the Chinese intend to carry the Olympic torch to the top on their way to Beijing.

By comparison, in the last 50 years, only 196 climbers have made it to the top of K2. This past summer, another 55 gave it a shot as six expeditions—from Kazakhstan, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic, plus one international group —converged on the south side of the mountain. Among them were some of the strongest mountaineers in the world, including the Czech climbers Radek Jaros and Martin Minarik, as well as Segarra and Ponce de Leon, who returned for another try. None of them reached the summit.

It was the second summitless year in a row, a statistic that, at least by the standards of Everest-level success, seemed to confirm K2's stature as the lesser giant. But among professional mountaineers who tackle the world's most formidable peaks, things look a bit different.

"People are drawn to Everest because everyone can understand the idea of 'the highest mountain on earth,' " says Greg Child, an Australian mountaineer and author who has summited both Everest and K2. "Christ, my grandmother can understand that. Unless you're on the inside of climbing, however, it's almost impossible to fathom an obsession with the second-highest. But K2 just has something about it. Partly it's the shape and beauty and symmetry of the thing. And partly it's the infamy—the stories of what's happened to people who've tried it: how fucked up they've become and how many have died. K2 is simply not an amateur's mountain."

K2's difficulties begin with its remoteness, reflected by the fact that the Balti hill people don't even have a name for the mountain. It was dubbed K2—K for Karakoram and 2 for the second peak in the range to be identified—by the British mapmaker T.G. Montgomerie in 1856. "Just the bare bones of a name," wrote the Italian alpinist Fosco Maraini in his 1959 book Karakoram: The Ascent of Gasherbrum IV. "All rock and ice and storm and abyss. It makes no attempt to sound human."

There are only two ways to reach K2. To get to the north side, which straddles the border between China and Pakistan, you first must fly to Islamabad, then drive 500 miles northeast to Kashgar, in China's Xinjiang province, then travel by jeep across the southern fringe of the Taklimakan Desert, then transfer to camels and caravan over the brown, broken wastes of the Shaksgam Valley. The more "accessible" southern approach requires slogging 40 roadless miles up the Baltoro Glacier in northern Pakistan.

K2's remoteness has other consequences. It sits eight degrees north of Everest, so the weather is considerably more vicious. "It's much colder, and great storms come shrieking off the mountain," says British mountaineer Jim Curran, author of K2: The Story of the Savage Mountain, the definitive history of the peak. "Unlike Everest, you almost never get a good, clean week to push for the summit."

Everest also boasts a well-established support infrastructure of guides and Sherpas who set up tents, fix ropes, and ferry canisters of supplemental oxygen to the high camps. On K2, there are few high-altitude porters or commercial firms—partly because of the isolation and partly because experience has demonstrated that guiding a mountain like K2 is an invitation to disaster. This point was proven yet again this July when a German climber named Klaus-Dieter Grohs slipped and fell to his death while pushing to the top. One of ten clients being led up the mountain by Kari Kobler, a veteran Swiss Himalayan guide who has climbed Everest twice, Grohs became the 53rd person to die on K2.

According to a 2000 study on high-altitude mountaineering deaths published in The American Alpine Journal, one in 29 climbers who summited Everest between 1978 and 1999 died on descent; on K2, one summiter in seven perished. "Those are pretty grim odds," says Raymond Huey, a professor of biology at the University of Washington who co-authored the study. "It's getting perilously close to Russian roulette." Things become even more dire when you compare summit fatalities among climbers who did not use supplemental oxygen: On Everest, the casualty rate is one in 12; on K2, it's nearly one in five.

That last number is rather chilling: Even among experienced mountaineers, K2 is more than twice as deadly as Everest. "Think of it this way," suggests Curran. "From Everest Base Camp, you can walk four hours and you're lounging on grass, drinking beer with trekkers. K2 stands absolutely on its own. The approach is hard. The base camp feels like the moon. The mountain itself looks utterly impregnable, and there's no easy way up the thing. And all this hits you between the eyes when you see it for the first time. It's like that famous Munch painting. You know the one—The Scream? Except, of course, you're the one doing the screaming."

FOR CLIMBERS, the existential angst kicks in the moment they round the bend into Concordia, the most majestic amphitheater of high peaks in the world. An enormous hub of ice situated six miles from base camp, where the Upper Baltoro and GodwinAusten glaciers collide, Concordia is surrounded by the crown of the Karakoram— Broad Peak and Gasherbrum I, II, and III—four of the 15 tallest mountains on earth, with an average height of 26,330 feet. To the east, the fluted ridges of Ladakh rise above the Siachen Glacier, the front lines of an ongoing border conflict between India and Pakistan. And if the weather is clear, a mountaineer will get his first glimpse of K2 directly to the north, filling up the sky, lustrous and giant.

"You're standing at 15,000 feet, and you're looking up at 28,000 feet," says Jim Wickwire, a 63-year-old climber from Seattle and a member of the first American team to summit K2, in 1978. "No photograph can do justice to 13,000 feet of vertical relief."

Nor can a photograph convey the ponderous immensity of a pile of rock and ice large enough to contain no fewer than 84 Matterhorns. "When I reached Concordia and saw K2, it literally stopped me in my tracks," recalls Rick Ridgeway, 54, who made it to the summit alongside Wickwire in '78. "It stopped us all—that mountain affects everybody in the same way. Nothing on the whole planet matches it."

Even Reinhold Messner, who at 59 is generally considered the greatest mountaineer of the 20th century, reserves a special measure of awe for K2, which he christened "the mountain of mountains" in 1979, after completing the fourth ascent of the peak. "It is the most beautiful of all the high peaks," Messner told me. "An artist has made this mountain."

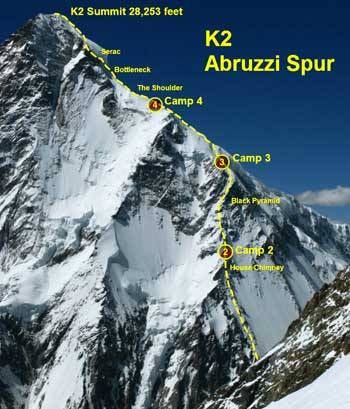

There are a handful of fiendishly arduous Himalayan peaks that pose even greater technical challenges than K2, the most prominent being Gasherbrum IV (26,000 feet) and the Ogre (23,900 feet), both located in the central Karakoram. Neither of these, however, involves the difficulties posed by the extreme altitude of K2, where even the most popular passage up—the Abruzzi Ridge—leaves no room for error. A steep spur on the southeastern side first explored in 1909 by Italy's Prince Luigi Amedeo of Savoy, Duke of Abruzzi, it involves more than 11,000 vertical feet of climbing and is approximately 20 degrees steeper than the South Col, the most heavily trafficked path up Everest.

Abruzzi made it to 20,500 feet—above where Camp 1 sits today—before abandoning his attempt. If anyone ever reaches the summit, he later declared, "it will be a pilot, not a mountaineer." But on July 31, 1954, two Italian climbers, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, topped out using Abruzzi's route. Compagnoni later claimed he heard the voice of an angel beckoning him to the summit; when he reached it, on his knees, he felt something on his face. "There was ice under my eyes," he later said in an interview. "I realized I was crying. Frozen tears."

He had good reason. Of the 196 climbers who have summited K2 since 1954, 144 arrived by way of the Abruzzi Ridge. And of the 53 people lost on the mountain since 1938, 36 perished somewhere along its spine.

The ridge begins with a line of towers that stretch up the lower part of the spur, ending in a 100-foot vertical fissure known as House's Chimney, named after Bill House, an American mountaineer who first climbed it in 1938. The pitch involves 5.6 rock climbing at 22,000 feet—the route's greatest technical challenge.

Above the chimney lies the Black Pyramid, a triangle of notoriously unstable slabs of ice and rock at about 24,500 feet. At the pyramid's apex, the route emerges onto the Shoulder, a broad hump at roughly 26,000 feet and the site of the fourth and final camp before reaching the top. It was here in 1986 that Al Rouse, the first British climber to summit K2, was overcome by exhaustion and abandoned by his companions in the middle of a six-day storm. Minutes after leaving Rouse, two Austrian climbers, Alfred Imitzer and Hannes Wieser, collapsed in the snow and died as well.

From the Shoulder, the summit is 2,250 vertical feet away. But reaching it involves negotiating a broad couloir often loaded with knee-deep snow; undertaking a delicate traverse out of the Bottleneck, a 100-foot ice-enameled couloir that steepens to more than 50 degrees; and then scaling an exposed traverse that drops 9,800 feet to the Godwin-Austen. At least ten people have died in the Bottleneck—including the Polish climber Tadeusz Piotrowski, perhaps the finest winter mountaineer of his day, who in 1986 lost both his crampons in the midst of a grueling descent from the summit, bounced off his partner, Jerzy Kukuczka (who managed to keep his footing), and hurtled off the face.

Finally, there are the snowy slopes of the summit helmet itself, which are broad and steep and, as anyone familiar with the gut-wrenching plummet of Alison Hargreaves and her companions in 1995 can attest, more than able to kill you.

DEATH AND IMPREGNABILITY have always been great motivators, of course. Not long after the Italians achieved their victory over K2 in 1954, India and Pakistan plunged into an extended period of fighting over their northern borders and closed off the central Karakoram; it was not until 1975 that foreign expeditions were permitted to return. Two years later, a 52-man Japanese expedition with 1,500 porters laid siege to K2, scaled the Abruzzi, and posted the second summit. A year after that, in 1978, an American team led by Jim Whittaker (the first American climber to summit Everest, in 1963) finally succeeded. Four men—Wickwire, Ridgeway, John Roskelley, and Lou Reichardt—made it to the top via a new route on the northeast ridge. The '78 expedition ushered in an era of breakthroughs on the mountain, including routes along the west ridge (Japanese-Pakistani, 1981), the south face (Polish, 1986), and the south-southwest ridge, which was summited that same year by Peter Bozik, a Czech, and two Polish climbers, Wojciech Wröz and Przemyslaw Piasecki.

K2's reputation as the most difficult and dangerous of the world's 8,000-meter peaks is surpassed only by the irrational pull it seems to exert upon climbers. No one understands this better than Wickwire, whose obsession very nearly cost him his life. When he completed his push for the top late on the afternoon of September 6, 1978, he was stranded on the summit face without a tent or sleeping bag as night fell, forcing him to endure 50-mile-per-hour winds and temperatures that plunged to minus 25 degrees—the highest solo bivouac up to that point.

"It was the only time in my climbing career that I really did let it all hang out, in the sense that I was going to get there no matter what," says Wickwire, who came down with pleurisy and had to have a piece of his lung surgically removed when he got home. "But I had this 20-year preoccupation with K2 in my dreams, and those dreams simply were not going to be denied. That's the power, the magnificence, of K2."

That magnificence can take strange forms. Weeks before he summited, Wickwire was descending with Roskelley to Camp 3, on the knife edge of the northeast ridge, when he witnessed the Specter of Brocken, a rare play of light in which a climber's silhouette is magnified and cast into the center of a cloud, sometimes surrounded by a double rainbow—two perfect circles, one inside the other. "That was the only time I've observed it in over 40 years of climbing," he says.

It was along this same ridge that Roskelley and Ridgeway found themselves enveloped one afternoon by a flock of orange-and-black butterflies that had wafted up on air currents. "They were everywhere," says Roskelley. "The world suddenly turned into this beautiful, orange, flapping mosaic of color."

Such moments can occur on any great mountain. But as commercialization threatens to overrun the highest peaks, these experiences become more elusive. K2's tendency to yield such ephemeral encounters partly explains why it draws a different type of climber than Everest—a climber who not only commands superior skills but harbors a deeper reason for wanting to be on the mountain. Greg Mortenson, who attempted K2 in 1993 after his sister, Christa, died at 23 of epilepsy, got as far as 25,000 feet but had to forgo his own summit bid to help an exhausted companion descend safely to base camp. Still, he has no regrets.

"I could have gone to Everest," says Mortenson, who went on to found the Central Asia Institute and spend the next decade building schools for young girls throughout northern Pakistan. "K2, however, seemed to better exemplify the freedom of Christa's spirit and my anger—my angst—over her death at a young age. On K2, you can't pay a guide service $65,000 to get you to the top. On K2, you need the experience, the skill, and the stamina to climb without these resources. Everest is a mountain for those who just want to climb to the highest point on earth. But K2 is more about philosophic heights. It's about purity, clarity, and being humble."

Perhaps no one fuses these elements more eloquently than Dr. Charles Houston, who led two of the earliest American attempts on K2. One morning, almost 24,000 feet up the Abruzzi Ridge during his second attempt, in 1953, Houston looked out of his tent. "It was about sunrise," he told me, "and the air was just filled with ice crystals. It wasn't snow; they were tiny, tiny ice crystals, and they were red and yellow and green and purple—all the colors of the rainbow. There were trillions of them, shimmering against the blue and black sky. It was a gentle and beautiful thing. And unforgettable."

This coming from a man who endured some of the most terrifying hardships on K2, and whose ordeal in 1953 has come to signify, more than any other, what it means to fail with dignity.